Originally published in Esquire in August 2014

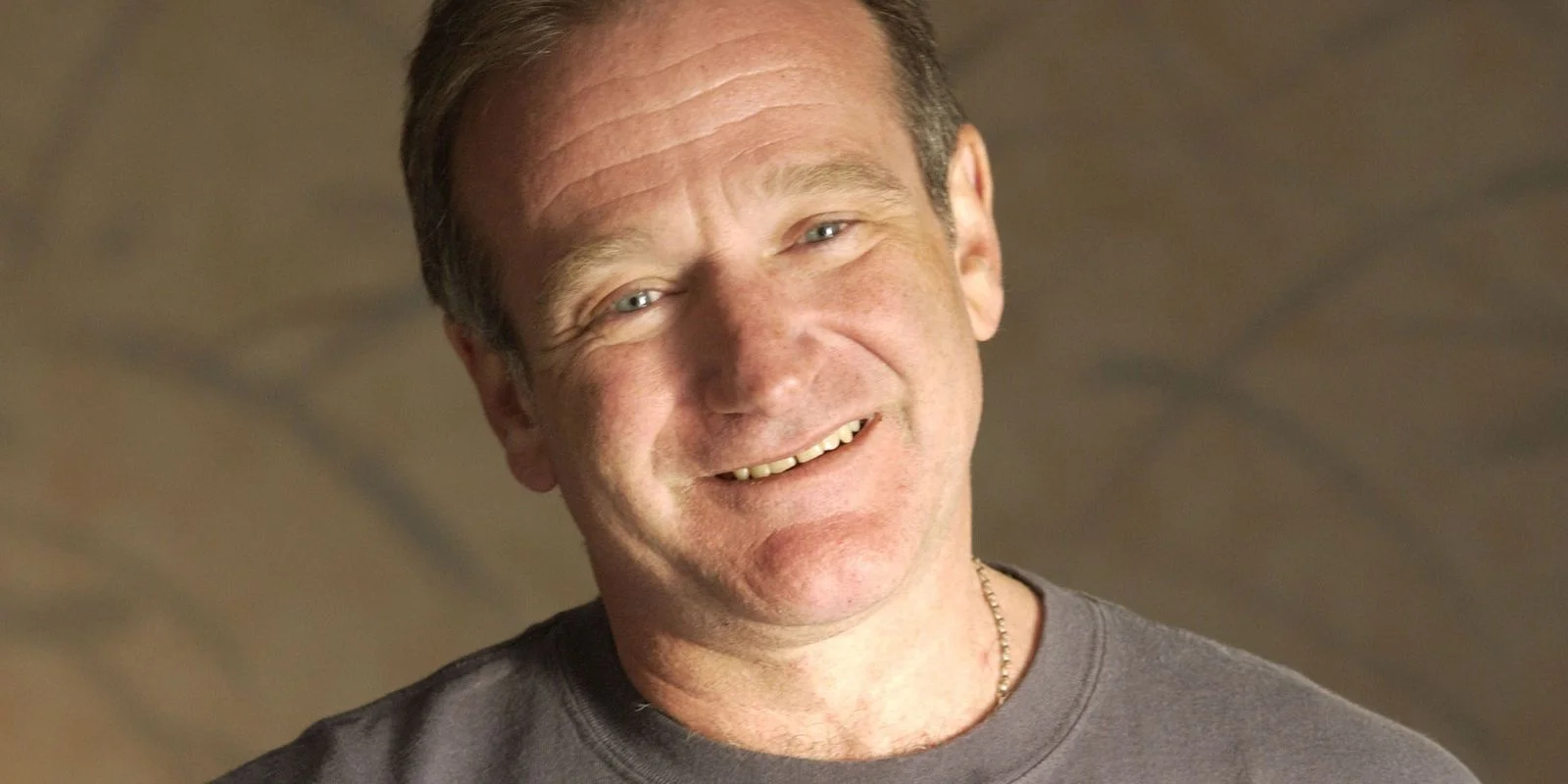

Though we all think we "knew" him from his work, the truth is there's so much we don't know about Robin Williams' life and why he died. One thing we know: They don't hand out Academy Awards(R) for dick jokes.

Celebrated, loved, and praised for so much of his life for being "manic," it maybe hurts more now for his friends and fans to think about how deeply, how painfully, he must have fought the darkness of depression. And to think now: He won his Oscar pretending to be a shrink called upon to help a gifted young man with a manic streak who couldn't shake the depressive.

My wife, Paula, and Robin's former wife, Marsha, met on the set of Mrs. Doubtfire in 1993 and have been friends for more than 20 years. As two of the few female producers on that film, they bonded early on during some of the quieter moments of production.

While it might be a stretch to say that Robin and Marsha Williams saved my life, it's no stretch to say that nearly 14 years ago, on a day that I got my shock diagnosis, Marsha and Robin and their friend and neighbor Chris Columbus helped convince me to move my newly-christened, Stage 3-advanced, colorectal cancer ass 1,250 miles from Colorado to San Francisco—in hopes of my receiving the best treatment I could possibly find.

It was not a roll-the-dice move. It turned out to be a reasoned decision made after the din died down that had more than a random Hollywood connection at its core.

At the time, Paula was working as an associate producer with Columbus on the first Harry Potterfilm. But we all had spent months together in the 1990s during the making of Doubtfire and Nine Months and Bicentennial Man in San Francisco. It was there, not in L.A., where Chris and Robin had both chosen to live—and it was there where they and Paula had held a number of film fundraisers and gotten to know some key people at the University of California-San Francisco, a top cancer hospital in the country.

UCSF was where I got my fourth and fifth opinions related to my cancer case. It is also no stretch to say it's where I met a few other people who wore white coats and who did save my life.

On and off through the 1990s, I shared dozens of dinners with Robin and Marsha, many of them on movie sets. Marsha's voice was always quiet, warm, and inviting; and still is. Back then, I was struck not by how loud Robin was in social situations, but how quiet and reflective he was at the dinner table. I remember being surprised by his deference to others in the room. That is, up to a point.... Time and again, sometimes an hour or two into the evening, he eventually would rise up and take over the room, launching into an improvisational sketch or two—or four.

That's the Robin Williams we all knew. Or thought we did. The quieter man was the one who visited his friend and Juilliard classmate, actor Christopher Reeve, immediately in the hospital in 1995 after the debilitating accident that made Reeve a quadriplegic; and who, along with Marsha, helped Reeve's wife, Dana, through the worst medical times of her own, including the lung cancer that took Dana's life in 2006 at age 44.

Then again, one day between takes on the set of Nine Months, while Hugh Grant was rather busy grabbing the headlines, I witnessed Robin talking on set with a brain-injured teenage girl in a wheelchair, who was working as an extra that day on a wedding scene. There was that soft, tide-pool voice again, softer than you ever heard on Leno or Letterman or on the umpteen years of Comic Relief. It wasn't a scripted moment. And he didn't just make a bit player's day. He made her year. I remember stepping back, moving out of the huddle, feeling I didn't want to intrude on their space.

From then, six years later and 45 pounds weaker, I found myself back in San Francisco, flat on a couch, a post-surgery cancer sad-sack survivor, moaning my way through recovery, wondering which goddam Ensure smoothie was gonna be the highlight of my day.... when Paula tells me Marsha and Robin are coming to visit after lunch.

Half a smoothie later, I make the mistake of telling Robin that the doctors who operated on my colon told me they had done a type of experimental surgery on my body. Turns out they used a 'nerve-sparing' wand—usually used for prostate, not colon, cancer operations—when they cut through and around my perineum to get some cancer out. And it's no stretch to say the perineum, sited perilously close to the prostate, is also the site of many bundles of nerves—nerves that transmit significant sexual pleasure and all sorts of get-up-and-go that helps forms erections. The docs were doing me One Big Favor.

When Robin heard that, he could sit quietly no longer. He bolted upright from the couch next to Paula and me and immediately—autonomically—placed his right elbow above his crotch, formed a tight tumescent fist, and started waving his wand back-and-forth, wildly to and fro, as if the surgeons had hit the wrong nerves, sending a spasmodic organ into erectile function disorder, one that was now leading a whole body around, one that wouldn't ever never quit.

Until, that is, Robin swerved around the glass coffee table, pulled a deft 180, and sat down swiftly.

I was howling and hurting by now. Trying not to laugh in the way you can't stop a sneeze that's passed its trigger point. But the truth is, I was also a bit scared: wondering whether the 42 metal staples holding my lower torso together would hold. I hadn't laughed this hard in months.

Then Robin became quiet again, as Paula and Marsha took back the floor, as I settled into my supine sprawl on the couch opposite the big screen TV that played ESPN for me eight-to-10 hours a day. That is, that was, until Comic Relief (home delivery edition) paid a little visit to my bedside.

Wouldn't it be something if Robin did have a hand—a full-length, out-of-control, arm erection parading around a cancer patient hand—in saving my life. Thing is, he sure made it worth living for a while.