BoCo Media collaborated with Ask Dr. Job, a blog that offers advice to people who face workplace challenges, such as finding new jobs, getting raises, dealing with superiors, writing resumes, and learning to ace interviews.

In Good Company?

YOUNG MVP! Tyler Blick Tackles ALL—Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

New York Times: As Survivors, We Were Closer Than Lovers

LESS than a minute after I arrived alone, on Amtrak from Manhattan, I knew this wasn't going to be easy. My ex-girlfriend, who was being as gracious as she could be after enduring a couple of years of cancer and four (partly successful) combinations of chemotherapy, was lighting a candle.

Or trying to. And it became clear in an instant: Her fingers wouldn't work. The matches kept bending, mushing, with each strike, before any whiff of sulfur. A side effect of her newfangled chemo regimen: neutropenia, neuropathy (or something similarly cruel-sounding) that deadens the nerves of patients' fingertips.

The candle was to be a nice touch, her warm way of welcoming me into her home, a loft in an artsy Philadelphia neighborhood where she went to live, and create, and create a new life for herself after her marriage, after the diagnosis, long after our short relationship.

But here we were together again, decades after our first hookup, because (we both knew but didn't say) there was a small chance this could be our last face-to-face meeting, our last hugs and goodbye. Especially if her next courses of breast cancer treatments didn't do what her A-list oncologist and the rest of us all hoped.

"We were exes-in-remission, reminiscing... a far cry from what we once had been: young, hungry, reckless-in-our-20's New York cITY Creative types."

Cancer survivorship was the other reason we were together again. She got her diagnosis at 43, the same age that I received a diagnosis of colon cancer. She had volunteered with the Young Survival Coalition, and a year later spied my Esquire article about my ordeal.

After a Web search or three, she found me. Now we were writing, talking, sharing bits of our lives again, glad that both of us were able to talk about our midlives (which we realized could very well have been our late lives).

We were exes-in-remission, reminiscing, sharing stories of white blood cell loss, hair loss, weight loss and adventures in vomiting. A far cry from what we once had been: young, hungry, reckless-in-our-20s New York creative types, carving out a place for ourselves in the city of too many roommates and too much competition with those chasing all-too-similar dreams.

Dream over, she suddenly relapsed the year before last. And went to inform human resources at her creative job. And went on disability. Pain took command, along with unruly lesions that surfaced in her liver. Soon we both knew she was in for a long, wicked ride to, we hoped, remission 2.0.

Time once again to board the slow chemo train, but this time with the newfound dread of less-forgiving odds — mixed like a medi-cocktail, with resolution, anger, hope. And not enough visible love, as even those closest to you at times pull away. Emotionally, physically.

It's uncomfortable at this point to say that I found a few of her notes flirtatious over the course of the last year; over the course of our chat-room-like e-mail messages minus the chat room. We were one-on-one. But especially as a guy in a good, solid marriage, I have no reason to lie: Once you sleep with someone, it's hard to ever get together with them again, no matter how much later, without thinking of the physical closeness that was, or wasn't quite, or might have been.

That's got to be the "love" in "making love" talking, even after so long, or else my thoughts of those long-ago nights spent together, so out of place in the here and now, wouldn't be troubling me today, amid all this sickness and sadness. I mean, should it take tumor metastases to allow us to fully feel such things and admit to them?

Back in her home, we took solace in the fact that we had made our own sort of mini support group, founded in part upon late-night e-mail notes and a call or two that consciously evaded mention of our long-ago love affair. There was a welcome lightness to our new friendship, a safe space.

When she pulls out the photo album, I ask, "Were we really that young?" ("Were we really that happy?" I think but don't say.)

After a while she opens up and tells me a bit about her ex-boyfriend: the one who left after her diagnosis, soon after telling her he didn't think he was the "caregiver type," though she claims her disease didn't cause their split.

My face crumples, incredulous, in protest. "Hey, at least I found out early on he wasn't The One," she says, in a more forgiving tone than I'd ever be able to muster.

"We don't say anything at all about how we broke up - or Too much about our current love lives, or family lives, either."

Later she adds, "It's sad that cancer had to be the catalyst." But now she's talking about how it brought the two of us together again.

Maybe so. But we also know that without our cancer, we probably never would have been together again. And certainly not like this: amid all the trappings of what might seem to outsiders like a romantic reunion, yet one that is socially permissible, even encouraged, given the circumstances.

These days, I find that survivor friendships like ours make you confront, early and often, the heavy and the light, and in so doing you find you are granted a curious kind of freedom. You shred the polite filters. You get a pass to cut to the chase. Because time together means more now.

After all, we became instantly closer in our mid-40s than we ever were in our early 20s, when she was an up-and-coming design student in art school, and I was a journalist sending all manner of suck-up notes to contacts at Newsweek, BusinessWeek, Rolling Stone, while trying to type my way out of trade journalism.

One bright fall day more than 20 years ago, she and I hopped a New York bus to the New Jersey Palisades. Over the George Washington Bridge we rolled, without having packed a lunch, or lugging even a single plastic water bottle (urbanites didn't yet hydrate like that). We went to walk some paths, take some pictures (in arty black-and-white), crunch some leaves under our desert boots. We made out a little, in PG-13 fashion, shrouded by a stand of stubborn oaks that hadn't shed their leaves on schedule.

NOW, on another brisk fall day, two major diagnoses later, sharing herbal tea in her urban loft space, we dish about magazines and photographers she knows; more about new times than old; about how parts of our bodies didn't (or don't) work so well when we were (or are) fighting our cancers.

We don't say anything at all about how we broke up, or much about our current love lives, or family lives, either. I feel "survivor's guilt" hanging heavy in the room, thinking it's unfair that I'm cancer free, five years after my nasty Stage 3, and she's suffering through the muck of her now-Stage 4, after reaching remission three years ago.

No guarantees, we know but don't say, for either of us. Let's do today.

Out of my backpack I share four magazines: Interview, Vogue, Entertainment Weekly, Vanity Fair. These, I had hoped, would appeal to the former art student who had lived in the Village near N.Y.U. with two other post-punk roommates when the Clash were the Coldplay of their time. She thanks me for bringing these pieces of the outside world in. Though now I wonder: If her fingers didn't work so well with soft matches, will they be able to easily flip 1,000 flimsy pages of advertising and articles? Will her eyes be able to handle the small type?

She's wearing glasses now, low on the bridge of her nose. She's wearing a wig, too, I see, although she doesn't mention it. She's also, through all this unfairness, looking somehow sexy to me, again. And this uninvited thought makes me feel old, confused, sad. But why shouldn't she? Are Stage 4 survivors not supposed to care how they look? What I know is: I hugged her so gently when I came through the doorway. Her body felt frail, unsteady, birdlike.

IN the fading afternoon light we talk for some time about her travels, her passion for Italy, Elsa Schiaparelli, and other things artful. Including some Euro-style photo shoots she had produced in the past few years while in her postcancer prime. After we order takeout Italian supper ("I don't drive these days," she says), we make our way into her bedroom, carrying brown paper sacks and fragile wine goblets.

Only then do I remember: When you have cancer and your body's racked from chemo (and serious opioids for pain), entertaining is hard. Even when it's an old boyfriend who believes he's low maintenance, who's been through this himself, who's supposed to know you don't stay more than two or three hours on these kinds of visits. You just don't. Because it's hard on stage-whatever patients — it upsets their (our) routines in the middle of such long low-light days.

As we move to, and onto, her bed, she one-handedly swings a stylish tray table over for us to share. I take note: This is a woman who's been taking many of her meals on this same Scandinavian tray table.

"Welcome to my Capri bed," she says, smoothing the tufted comforter. What she means is: She took the money she had been saving for a (canceled) trip to Capri and bought this remote control bed instead.

I settle in, best I can, in the cold and dark next to her. Then I immediately bounce back up to forage for napkins, trying to be useful. With our fingers we eat pizzetta; with our eyes we blankly watch CNN. Then we talk a little about, God help us, Joe Biden's politics. And a comfortable silence envelops us, despite the nonstop cable chatter. It's a reconnection, a spark, however slight.

I take a swirl-sip of the fragrant French wine that my ex-girlfriend has just poured for me. Didn't notice: was it from a "good year"? No real reason to ask. Pretty much every year seems a good year about now. My back hurts a little as we sit scrunched side by side, moving our forks around. Outside, windblown leaves dance in the dark. Then I take another sip of, I don't know, Bordeaux. I can't taste it. I can't taste anything.

Article first published August 12, 2007 on the NY Times website and A version of this article appears in print on page ST6 of the New York edition with the headline: As Survivors, We Were Closer Than Lovers.

5 operations you don't want to get -- and what to do instead

My Cancer Story: Part One

PROLOGUE (2001): MAD COLON DISEASE

At first, I thought it was the lousy British food. I had landed in London in mid-June and succumbed to a wicked case of jet lag. Or so I thought. A week, two, then three went by, and still I wasn't sleeping through the night. Restless; not in any pain, just not sleeping, and I hadn't been eating all that well, either. "Bangers and mash, buddy?" Not hardly . . . My wife, Paula, and I had arrived in the UK last summer, set to stay for the better part of a year. She would serve as associate producer on the Harry Potter film; I'd write from overseas, traveling back and forth to the States when necessary for work. . . . After a month or so, my sleep still somewhat restless, I notice I've lost some weight.

Chris Columbus, the director [Home Alone, Stepmom] and longtime friend of mine and my wife's, asks Paula one day at dinner if I'm okay; he sees I've lost weight, too. I also start to feel occasional cramps in my stomach, or lower, even, down toward my groin. Upwards of my perineum, maybe, somewhere the hell down there. . . . I also have diarrhea at least a couple of times a week (British toilet paper sucks, by the way--c'mon, the war's been over fifty-five years), which I attribute to not only the plebian British food but to the pints of warm ale that I'm trying to get used to, nightly, at the local Haverstock Arms pub. No health ignoramus, I decide to call a doctor in London to see if what I have is a flare-up of colitis, the disease I was diagnosed with--and treated for--back in New York in 1982. I find a doc fairly easily, at the Wellington Hospital, which in the two-tiered health-care system in England seems to me to treat the moneyed tier . . . (tea and biscuits in the lobby while we wait).

Looking back, I can say that both Dr. Wong and I get home that night thinking I have a case of colitis. Turns out we were wrong. We've all heard of mad cow disease--mad colon disease, maybe?

THE DIAGNOSIS [Part I]

INTERIOR: Master bedroom of our Boulder, Colorado, home, focus on phone on nightstand next to bed.

EXTERIOR: Wickedly bright sunshine, some clouds over the Flatirons and foothills.

CUE SOUND: Phone rings.

"Hello."

"Mr. Pesmen?"

"Yes. . ."

This is my doctor, my gastroenterologist, I can tell, on the line.

"Mr. Pesmen . . ." (Uh-oh, he's said my name twice in five seconds; not a good sign when you've been waiting for five hours for a phone call from someone who has been waiting for results from the pathology lab. . . .)

"I've got some bad news. . . ."

SYNOPSIS: This is no screenplay; this is not the theater. This is (my) real life. It has just been threatened. . . .

SKATING AWAY [PART I]

For some reason, after I hang up with the doctor, I decide to go ahead and go ice-skating, just like I'd planned, with my friend Tom and his daughter in downtown Boulder. Call it denial, shock, incomprehension. For now, I still feel strong, I don't want to call or talk to anyone. . . . Paula isn't home . . . maybe being on the ice will somehow soothe me. I am lost, but head downtown with my skates in my hands. I park the car, lock up, and hear tinny speakers blaring "Jingle Bells." Three days till Christmas. . . .

THE DIAGNOSIS [Part II]

SCENE: Master bedroom, still. "It turns out they found some cancer cells in there," the doctor says of the pathologist. "I am really sorry."

I am stunned but do not cry. Instead, my body convulses slightly. Sitting on my bed, hunched over the phone, I feel as if I've just been in a minor car wreck . . . but all's . . . almost . . . okay. My journalistic instincts take over and I start taking notes furiously . . . "adenocarcinoma . . . second opinion . . . final pathology report after the weekend . . . need to get you to a good surgeon . . . don't know the stage yet . . . after surgery you'll know more . . .-really sorry to give you this news. . . ."

Merry Christmas.

SYNOPSIS: Forget the car wreck. Feels like I have been hit by a train and have entered another world. I am now a cancer patient. December 22, 2000.

SKATING AWAY [PART II]: MY SECRET

For an hour and fifteen minutes, I don't tell a soul. I skate and make small talk, waiting for 4:00 to arrive, when I'm supposed to pick up Paula at a friend's. She knows we've been waiting for the call and, as soon as she hops in the car, asks me if I've heard anything. I lie and say no. My secret for ten more minutes. I don't want to tell her until we get home. I feel like an asshole, lying to my wife about something so important, but I tell myself I'm doing it for her comfort.

When I tell her, we're in the kitchen, seated at the kitchen table.

"Paula," I say, "the doctor did call." Pause. She looks at me as if she is extremely hungry, though I know it is a look of fear.

"What? What?"

"I have cancer," I say. And nothing more.

She starts breathing heavily, then starts to shake. She starts to cry, I don't yet, then can't help but join her. Then she says she has to get down on the floor, right here, right now, or else she may faint.

My wife is now flat on her back on our white-tiled kitchen floor; we are both crying-heaving-crying, and I cradle her head in my hands and tell her to keep breathing.

"It's going to be okay," I say, not knowing if it will.

My wife and I both are now on the kitchen floor, letting this news sink in.

THE DIAGNOSIS [PART III]

SCENE: Downtown Denver, four-story medical building.

INTERIOR: Surgeon's office.

"You have rectal cancer, a kind of colon cancer," Doctor Second Opinion says. A weird dude to my eyes, kind of jumpy and unsettled, this overeager surgeon has a good reputation among his peers. Plus he's one of the few docs we were able to see over the holidays. . . . Weird Dude Doc, after doing a rectal exam, then sits me in another room and compares my tumor to a rather large, gnarly bonsai tree that's thriving in a pot on his windowsill. He starts talking about growth, and I'm not liking this analogy at all. "This man will not operate on me," I think as I take copious notes, realizing that surgeons' skill often has little to do with their personalities. . . .

CUT TO: The University of Colorado Health Sciences Center.

INTERIOR: Exam room of Dr. Third Opinion, Robert McIntyre, M.D.

"I agree you have rectal cancer," Dr. McIntyre of the University of Colorado says. "The question is how much of the colon will we have to remove. . . ." I like this guy, his manner, his calm demeanor, his apparent mastery of the diagnosis with only limited information, which is why he's prepping me for a series of CT scans later this day, ordered by Dr. Cory Sperry, a friend of ours and a friend of his, to see if any cancer has spread to my lungs, abdomen, or liver. . . . This guy could operate on me, I think. And after he calls two days later to tell us the CT scans look "good . . . I see the tumor, but the lungs, abdomen, and liver look clear," Paula and I feel like we've been given a reprieve. Good doc. Good results following a horrifying few days, and aftershock. Now, maybe, we can set up a plan to kick this cancer's ass, to turn perhaps the wrong phrase. . . .

SYNOPSIS: I try to focus on some of Doc McIntyre's last words to Paula and me as we huddled in the exam room: "Cancer is a word, not a sentence." I'm curable.

TOUGH CALL

Waiting. And wondering why I'm sitting on my bed on Saturday morning, delaying the inevitable. Waiting to call my family in Chicago and tell them the news. Making the wrong call and the right call at the same time, deciding to start by calling my sister, Beth. After all, she's my only sibling, just a couple of years older, forty-five, and has been through a major assault, having lost her first husband, Art, to leukemia when he was thirty-five and she was thirty-two. A rock then; I expect her to be a rock now.

"I have cancer," I blurt after we chat about who-in-the-hell-remembers for about a minute. A slight pause. Longer pause, then a mournful wail and sob and heaving of breath and sound and emotion I have never heard emanate from my sister. Or from anyone close to me. Positively frightening. I'm now shaking, taking this in, realizing that maybe I've touched a dormant nerve that reached right back to that day when she became a widow, in July 1988.

Haunting, her sobs. "No! Noooooooooo, noooo!" And then she recovers. And then we settle into the shaken rhythms of our breathing, somehow feeling stronger, if only for a minute. I grab Paula's hand a little tighter while we buck up and prepare for The Next Call.

At sixty-nine and seventy-two, my mom and dad, Sandy and Hal, are to me a model couple. Semiretired, semihip (my mom can still pull off leather pants; my dad, a leather bomber jacket), semiserious about fitness, and married happily for nearly all of their forty-nine years together. I've got to "protect" them but can't delay any longer.

"I'm okay," I tell my mother as she asks, rhetorically, how I am. A signal from son to mother. She knows "okay" means something's wrong, though she turns out to be a rock. "I have cancer," I choke out to her, wondering if the fact that her mom died of cancer at forty-one, when she was only nine, has somehow steeled her against some of the worst medical news she could hear. My dad is a different story. He takes in the diagnosis, breaks up, then says, "You . . . have my colon." He repeats it. I'm confused, as my father has never had intestinal problems. He hands the phone off to my mom, shaken, and she tells me we will get through this and come out the other side. . . .

Weeks later, I learn what my father was trying to tell me through emotional upheaval: "You can have my colon." At a literal loss for words, he was telling me he was willing to donate his, or part of his, large intestine to me, no matter how unlikely a scenario this could ever be. I'm glad I didn't know what he meant at the time.

NOT HOME ALONE

After Paula e-mails Chris Columbus and a few other people she's working with on the Potter movie, Chris calls our home immediately. He has put in calls to friends, including Robin and Marsha Williams, in San Francisco, to try to help us get fourth or fifth opinions at University of California, San Francisco, a top cancer center and the one that the Columbuses and Williamses have the utmost trust in. . . . It's also the hospital where Paula has some strong contacts, from years of helping coordinate movie screenings and benefits that have aided UCSF fundraising.

Almost unbelievably, Chris and his wife, Monica Devereux, immediately offer us the use of their home in San Francisco if we should choose to go there for treatment. And within hours, Marsha Williams is on the phone with Paula . . . then me . . . talking about how important it is to get the best doctors for cancer treatment . . . and that she knows how to help us find them at UCSF. An unlikely Hollywood connection to my cancer, I am thinking, but there is friendship at the core of these gestures, not glamour or glitz. I am amazed at the outreach that's seemingly coming into our world, one call at a time. . . .

HAPPY BIRTHDAY

Lashing out at Doctor Dickhead in our darkened bedroom back in Boulder. We're home, "relaxing" and packing, getting used to powerful pain meds (and stool softeners to counteract their constipatory effects), and I'm still angry, I realize through late-night sobbing, at the doctor who shall remain nameless, for now, who calls himself a gastroenterologist but did not, four to five months ago (after Dr. Wong's bloody finger and recommendation of a sigmoidoscopy), perform even a digital rectal exam that should have discovered this two-inch-long "locally invasive" tumor. Laziness? Maybe. HMO pressures to see too many patients per hour? Doubt it. The asshole didn't see fit to look in mine, as most competent gastroenterologists would suggest. I stop crying, settle down for a long fight, and try to find grace in this situation on a day that is probably the worst birthday my wife Paula has ever endured.

I'm prone most of the day and unable to get to the store to buy a card or present for my partner, the love of my life, who cries as I present her, shortly after midnight, with a thirty-ninth-birthday card with thirty-nine hand-drawn hearts that I've fashioned from a folded business card of mine, drawing and writing in the bathroom between our two sinks. Happy fuckin' birthday indeed.

FUTURE BEST-SELLER?

My best friend, Geoff, whom I've known since 1970, calls from Chicago: "I got an idea," he says. "You can do a book, call it: Me, Cancer, and Geoff. Instead of a book about how you and your wife got through this together, it'll be a buddy book about how I helped you kick cancer. I'll be calling you every day; people aren't expecting that." Pause. "You're sick," I say. "I know," he says. "But I gotta ask you: Does this mean I'll have to do one of those Run-Walk things with you in five years?"

THE DIAGNOSIS [PART IV]

SCENE: Exterior UCSF Surgery Faculty Practice building, 400 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco.

INTERIOR: Office of Dr. Mark Lane Welton, colorectal surgeon.

". . . I believe your case is not a slam dunk, but I don't think it's one of my fourteen-hour operations, either," Dr. Welton says in the first hour of our meeting. "It's probably a three- to four-hour operation."

We soon learn that the cancer was found very late.

"Your cancer is advanced," Dr. Welton tells us.

"Then why didn't they find it in my screening three years ago?" I snap.

Dr. Welton shakes his head and tells me, "I'd guess it's at least five years old."

SYNOPSIS: He's confident surgery will cure me, but he won't openly rip his colleagues. (Seems he believes Dr. Dickhead and other private-practice gastros aren't as adept in colonoscopy as many practicing docs at university med centers, such as UCSF.) I like his style and honesty. If I have to be cut up, I want Dr. Welton to do the job.

PROBING MY NODES

Lying on my back, waiting for doctor whomever from UCSF "paths" (pathology) to enter the room to do an FNA (fine-needle aspiration) of my inguinal lymph nodes, down by the groin and perineum, where the body normally doesn't invite needles in . . . poke, dig, poke, dig, poke, dig, he does. All negative--great! No cancer cells found. But he has to probe each one again, he tells me, a second time, to be "more sure."

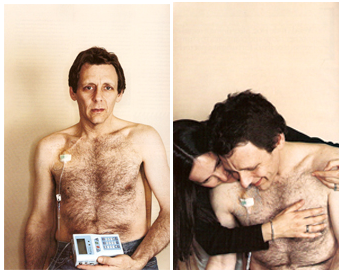

Great, I'm thinking, and Dr. Daphne is still planning to zap my nodes anyway, with God knows how many radiative "Grey," for good measure, I later learn. . . . Gotta rush so the next docs can operate on me and insert a chemotherapy "port" in my chest . . . then Paula's gotta toss me on a United plane and fly my ass home for the weekend. Looks like we've made the choice; San Francisco for my treatment and surgery, back home to Colorado for the healing.

Medical Experts in this article are not pictured here.

THE TEAM

Learning, in a hurry, that when you have cancer you don't have just one doctor. In my case my team includes:

Alan Venook, M.D., medical oncologist, UCSF

Mark Lane Welton, M.D., colorectal surgeon, UCSF

Daphne Haas-Kogan, M.D., radiation oncologist, UCSF

Jonathan Terdiman, M.D., gastroenterologist, UCSF

Jerry Ashem, nurse, home chemotherapy provider, Life Care Solutions

Nancy Rao, N.D., naturopath and accupuncturist, Boulder, Colorado

Paula DuPré Pesmen, associate producer, wife, partner

EIGHT WORDS YOU DON'T WANT TO HEAR

It's something I won't soon forget . . . there I am, splayed out on a hard exam table in the radiation-therapy room, hospital pj bottoms pulled halfway down my crotch . . . when a senior member of the rad/oncology team addresses a younger doctor after viewing my simulation--the precise position I will be in when radiation beams will enter my body.

He uses eight words:

"The penis is going to have a reaction."

In other words, the penis (which would be mine) will very likely develop a sunburn of sorts, perhaps over six weeks of absorbing nearby radiation waves. Note to self: "Prepare."

TREATMENT: CHEMOTHERAPY

Surprise: In this new new age of personal electronics, it appears that my six weeks of chemotherapy will be administered by a machine, not a person.

Small enough to fit in a fanny pack, Palm Pilot--ish in personality, the portable pump I name Abbott, built by Abbott Labs outside Chicago, will be in charge of delivering a toxic chemical, a toxic cancer-fighting chemical, 5-fluorouracil, into my bloodstream. (I could opt for weekly visits to an infusion center, where my medical oncologist has his office, but since I'm on a low-dose regimen, Abbott seems the way to go.) He's got a small screen, twenty-four buttons, lots of chirps and beeps, and a clear plastic tether tube that stretches about four and a half feet.

Once a week, a home nurse will come and change the medicine, flush my "line," take my blood pressure, draw some blood, change his gloves, don a mask, change the needle that fits in the port inside my chest, swab the whole upper-right quadrant of chest with antiseptic, then tape me down, making me water-resistant, not quite waterproof, for at least six weeks. More chemo later? I wonder. . . . Yes, I learn soon enough, but it probably won't be porta-pumped in.

TREATMENT: RADIATION

Beep. Beep. Beep. Beep.

Whirr. Whirr.

Bzzzzz. Bzzzzz. Bzzzzz. . . . Silence. Ker-chunk. . . .

Welcome to the world of Radiation Oncology, Day One of the six-week treatment, as part of a protocol that's not practiced everywhere. Some docs say, till more data are in, the tumors should be taken surgically first, followed by chemo and radiation. But not the docs we have on our team. It's a sandwich kind of cancer-fighting. BEEP/WHIRR, then surgery; then chemo afterward, as necessary.

Today, in the basement of UCSF's Long Hospital, amid the city's first big storm of the year, I try to find a quiet moment as the Big Gun goes off. Beep, Beep, Beep. Whirrr . . . Bzzzz . . .

TREATMENT: RADIATION

Wondering why some people are so afraid to use the word cancer when they e-mail or write notes to me sending warm thoughts. . . .Thanking the literary lords that a ten-year-old daughter of one of my friends sent a card that said, up front: "Dear Curt, I hope you fight off your cancer. . . . Love, Rebecca"

How the hell can you take this fucker on . . . if you can't call it by its name? It's cancer, and I'm hooked up to a porta-chemo-pump stashed in a fanny pack that's "pretreating" my tumor while I get daily blasts of radiation (weekends off), courtesy of the GE Clinac 2300 radiotherapy accelerator. I'm a 24/7/6 (six months total treatment) anti-cancer assault unit, with all this technology comin' at me, going in me, going through me and God knows where else into the walls of the underground radiation oncology unit named for Walter Haas, the Levi Strauss magnate, and dedicated in 1983.

Otherwise, it's January 2001, and, shit, things are great.

EAT MORE, WEIGH LESS

Weighing in one afternoon while in treatment at 168. Wondering where the pounds went so quickly. I was 183 before I left for England last summer. My appetite is down, so is my general attitude toward eating. "Food is no longer for pleasure," Dr. Haas-Kogan ("Call me Daphne") says. "It's your job."

SEX AND MY CANCER

Haven't found lots of info on the standard patient Web sites about sex and colon cancer. . . . Here's what I know so far: In one month of being a colon-cancer patient, I've had sex twice, once what I would term successfully. The other time, well, that's what I know about sex and my cancer.

HAPPY F'KIN ANNIVERSARY

One month after the diagnosis. My anger has dissipated toward my dickass doctor who never stuck his middle finger up my anus all fall 2000, while I complained of rectal pain--it's right there in his carefully written notes in the records I snatched, or rather requested, from his office. I mean, of course my anger has cooled. . . .

Consider: A patient at higher-than-average risk of colon cancer comes in and complains of stomach pain, rectal pain, and diarrhea (some would call that "a change in bowel habits . . ."), and in your wisdom you decide not to perform a basic digital rectal exam. Cruel irony, perhaps, that the cancer you'd later find would show up in the rectum. And was, other surgeons have said, large enough to have been felt by a doctor's finger. . . . And if you had glanced through my records, you would have seen that you performed a screening colonoscopy on me a few years ago, and that I had some suspect tissue that turned out to be benign. No need to check back, I guess. I know how hard doctors have to work these days.

Four or five months earlier, diagnosis would only mean I'd be a lot more comfortable right now and have a better--as hard as it is to say--chance of cure, whatever that means in oncological parlance. You can have your five-year survival rates, Dr. Dickhead. You've called me exactly once in a month's time to check on me, your patient that you recently diagnosed as having colon cancer. Remember me? Happy f'kin anniversary. Maybe see you in court.

"A POSSIBLY FATAL EVENT"

Guinea-pig Friday. Seven hours of waiting for a cautionary scan of my lungs and legs, all because I reported having shortness of breath this morning and my surgeon, Dr. Welton, and his resident scrunched their eyebrows like squirrels (if I'm a guinea pig, they're squirrels) and thought of the remote possibility of PE--pulmonary embolism--"a possibly fatal event."

I have a few risk factors, you see: an open line running into my veins for chemo; I have cancer; I am over forty years old; have an infection; and have been largely immobile. Better safe than dead, they think but don't say. (Reportedly, it's one of the most frequently missed diagnoses in medicine.) So there goes our Friday afternoon and evening. We wait, and wait, for a space in the CT queue . . . and Doc Daphne comes over from the hospital next door to try to help move things along . . . at 8:00 P.M. on a Friday night. Three kids she has at home, and she's with Paula and me. This is what you call care. This is what leads to Paula getting for her four Harry Potter T-shirts from her stash in London. My lungs and legs turn out to be clear.

A SOB STORY

Waking up with bad chemo/radiation nausea and diarrhea . . . an hour on the john to start the day . . . followed by thirty minutes of intense sobbing in bed, broken occasionally by heavy breathing (to relax me), the tears flow and I plead for "a break." I know part of this frustration is from yesterday's seven hours of helplessness and waiting for exams . . . and the possibility of "a fatal event," as if colorectal cancer isn't a possibly fatal event. I begin to view crying as part of healing. It's probably in the cancer-support books that the nurses gave me and that I've yet to read . . . Fourth, you cry.

LICK ME

After too many days of chemo/poison pumping through my veins, my body sends its first signal of being pissed off at the assault--a rash, or rawness, on the back and center of my tongue, all raised and ugly, what the doctor calls "mucousitis"; what a nurse says might be thrush . . . we'll worry about it tomorrow. Today, I'll just add some antibiotics to my arsenal to try and hit the elusive fever that kicks up each afternoon and evening, from 99.4 to 100.5 or so, possibly related to last week's discovery of an abscess. "Possibly," says Dr. Daphne and Dr. Welton. Lotsa possiblys in this long-term anti-cancer contest that's still in the early stages. Even a temporary alarm set off by Abbott--signaling occlusion in the tubes that send 5-FU chemo drug into my body--doesn't trip us up for long.

An 800 number, plus a knowing pharmacist on the "home health care/Life Care Solutions" hotline, helps us get Abbott back on track with only a ten-minute interruption in cancer-kick-butt service. With ER playing in the background on TV, my little emergency couldn't have asked for a more macabre backdrop. Blood and guts all over the Mitsubishi big-screen TV . . . a portable-CD-player-sized pump in my hands, sending peeling alarm signals and not responding to my attempted repair. And I can't very well call Dr. Greene.

I DON'T LIKE MONDAYS . . .

Setting the alarm for 8:45 A.M., which to the rest of the world sounds late, I know, but for someone who is woken up every two hours to take a piss because radiation waves have riled up my bladder tissue till it's as angry as an eighty-four-year-old's who's got a mean case of prostatitis . . . truth is, I don't want to arise at 8:45. I could easily sleep till 10:00, since I haven't enjoyed real REM-type sleep for what seems like a week.

Waiting for nurse Jerry, all earnest and bearded and careful and responsible-like, to come visit and slip on the rubber gloves and rip a bent needle out of the port that's been surgically implanted in my chest . . . new week, new bag of "dope" for my main man, Abbott. . . . It's all good, I suppose, but I don't enjoy lying flat on my back with anti-splash pads beneath my chest and torso. (Chemo is poison, let's remember; we don't want that shit splashing about the linens, much less our respective skins. . . .)

Mondays mean a whole week ahead of whomping the bad cells with good X rays and 168 milliliters of 5-fluorouracil cocktail, my chemo drug of choice . . . so by Friday night or Saturday morning, I will almost certainly feel like shit. Which means, they tell me, Mondays should actually be "good" days, because I've had the weekend off from the radiation assault . . . and my body's had a chance to "recover."

Shit, other than that, Mondays are fine specimens of the week. When you're normal, that is. When you're Cancer Boy, you're just a bit more skeptical about this fine day. . . .

BONDING

Flipping off a friend, in a good way, a male-bonding way, as I lie on the couch, fatigued and diseased. He's flown twenty-five hundred miles to visit me, my old roommate Todd, and at one point I look over at him in the living room, our eyes meet, and I give him the finger. He understands completely. What men want. A tough way to say, "Thanks for leaving your job and family for a few days to come hang with me as I get chemo'd and radiated." A guy thing. I love the guy. He's here. I'm hurtin'. So "Fuck you." Makes perfect sense, as Paula wonders, maybe, what in the hell I've just done to my friend. She understands, maybe not completely.

CAN CANCER BE EMBARRASSING?

An East Coast friend, whom I've known since 1980, calls: "So . . . it must be hard having cancer in a place that's embarrassing?"

I pause, weighing the absurdity of the comment, then respond.

"I guess so. But I guess I'd rather have colon cancer than brain cancer." Insensitive motherfucker, I am as well, knowing that I disrobe every day in the bowels of UCSF's Long Hospital alongside patients who are being treated radiotherapeutically for cancer in and on their brains.

That's not so embarrassing? I wonder. And we go on to talk about, believe it or not, the New York Yankees.

SUNBURN WHERE THE SUN DON'T SHINE

"It's gonna get worse before it gets better," says Doc Daphne as I hit the home stretch of "Intro to Radiation 101" (six-week course). Sunburnlike burns on my inner buttocks, burned and raw skin where groin meets thigh, and, yes, a scorched penis. Time to learn, from the radiation nurse, how to use and apply the wickedly priced, aloe-based ointment known as: Carrington RadiaCare Gel Hydrogel Wound Dressing. It's soothing, I soon find, as I hitch up my drawers and shuffle off after getting dressed, holding my wife's left hand in my right.

Article first published in Esquire May 2001 | Volume 135 No.5 and is also available on the Esquire website