THE TEAM

Learning, in a hurry, that when you have cancer you don't have just one doctor. In my case my team includes:

Alan Venook, M.D., medical oncologist, UCSF

Mark Lane Welton, M.D., colorectal surgeon, UCSF

Daphne Haas-Kogan, M.D., radiation oncologist, UCSF

Jonathan Terdiman, M.D., gastroenterologist, UCSF

Jerry Ashem, nurse, home chemotherapy provider, Life Care Solutions

Nancy Rao, N.D., naturopath and accupuncturist, Boulder, Colorado

Paula DuPré Pesmen, associate producer, wife, partner

EIGHT WORDS YOU DON'T WANT TO HEAR

It's something I won't soon forget . . . there I am, splayed out on a hard exam table in the radiation-therapy room, hospital pj bottoms pulled halfway down my crotch . . . when a senior member of the rad/oncology team addresses a younger doctor after viewing my simulation--the precise position I will be in when radiation beams will enter my body.

He uses eight words:

"The penis is going to have a reaction."

In other words, the penis (which would be mine) will very likely develop a sunburn of sorts, perhaps over six weeks of absorbing nearby radiation waves. Note to self: "Prepare."

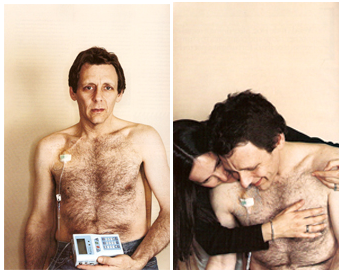

TREATMENT: CHEMOTHERAPY

Surprise: In this new new age of personal electronics, it appears that my six weeks of chemotherapy will be administered by a machine, not a person.

Small enough to fit in a fanny pack, Palm Pilot--ish in personality, the portable pump I name Abbott, built by Abbott Labs outside Chicago, will be in charge of delivering a toxic chemical, a toxic cancer-fighting chemical, 5-fluorouracil, into my bloodstream. (I could opt for weekly visits to an infusion center, where my medical oncologist has his office, but since I'm on a low-dose regimen, Abbott seems the way to go.) He's got a small screen, twenty-four buttons, lots of chirps and beeps, and a clear plastic tether tube that stretches about four and a half feet.

Once a week, a home nurse will come and change the medicine, flush my "line," take my blood pressure, draw some blood, change his gloves, don a mask, change the needle that fits in the port inside my chest, swab the whole upper-right quadrant of chest with antiseptic, then tape me down, making me water-resistant, not quite waterproof, for at least six weeks. More chemo later? I wonder. . . . Yes, I learn soon enough, but it probably won't be porta-pumped in.

TREATMENT: RADIATION

Beep. Beep. Beep. Beep.

Whirr. Whirr.

Bzzzzz. Bzzzzz. Bzzzzz. . . . Silence. Ker-chunk. . . .

Welcome to the world of Radiation Oncology, Day One of the six-week treatment, as part of a protocol that's not practiced everywhere. Some docs say, till more data are in, the tumors should be taken surgically first, followed by chemo and radiation. But not the docs we have on our team. It's a sandwich kind of cancer-fighting. BEEP/WHIRR, then surgery; then chemo afterward, as necessary.

Today, in the basement of UCSF's Long Hospital, amid the city's first big storm of the year, I try to find a quiet moment as the Big Gun goes off. Beep, Beep, Beep. Whirrr . . . Bzzzz . . .

TREATMENT: RADIATION

Wondering why some people are so afraid to use the word cancer when they e-mail or write notes to me sending warm thoughts. . . .Thanking the literary lords that a ten-year-old daughter of one of my friends sent a card that said, up front: "Dear Curt, I hope you fight off your cancer. . . . Love, Rebecca"

How the hell can you take this fucker on . . . if you can't call it by its name? It's cancer, and I'm hooked up to a porta-chemo-pump stashed in a fanny pack that's "pretreating" my tumor while I get daily blasts of radiation (weekends off), courtesy of the GE Clinac 2300 radiotherapy accelerator. I'm a 24/7/6 (six months total treatment) anti-cancer assault unit, with all this technology comin' at me, going in me, going through me and God knows where else into the walls of the underground radiation oncology unit named for Walter Haas, the Levi Strauss magnate, and dedicated in 1983.

Otherwise, it's January 2001, and, shit, things are great.

EAT MORE, WEIGH LESS

Weighing in one afternoon while in treatment at 168. Wondering where the pounds went so quickly. I was 183 before I left for England last summer. My appetite is down, so is my general attitude toward eating. "Food is no longer for pleasure," Dr. Haas-Kogan ("Call me Daphne") says. "It's your job."

SEX AND MY CANCER

Haven't found lots of info on the standard patient Web sites about sex and colon cancer. . . . Here's what I know so far: In one month of being a colon-cancer patient, I've had sex twice, once what I would term successfully. The other time, well, that's what I know about sex and my cancer.

HAPPY F'KIN ANNIVERSARY

One month after the diagnosis. My anger has dissipated toward my dickass doctor who never stuck his middle finger up my anus all fall 2000, while I complained of rectal pain--it's right there in his carefully written notes in the records I snatched, or rather requested, from his office. I mean, of course my anger has cooled. . . .

Consider: A patient at higher-than-average risk of colon cancer comes in and complains of stomach pain, rectal pain, and diarrhea (some would call that "a change in bowel habits . . ."), and in your wisdom you decide not to perform a basic digital rectal exam. Cruel irony, perhaps, that the cancer you'd later find would show up in the rectum. And was, other surgeons have said, large enough to have been felt by a doctor's finger. . . . And if you had glanced through my records, you would have seen that you performed a screening colonoscopy on me a few years ago, and that I had some suspect tissue that turned out to be benign. No need to check back, I guess. I know how hard doctors have to work these days.

Four or five months earlier, diagnosis would only mean I'd be a lot more comfortable right now and have a better--as hard as it is to say--chance of cure, whatever that means in oncological parlance. You can have your five-year survival rates, Dr. Dickhead. You've called me exactly once in a month's time to check on me, your patient that you recently diagnosed as having colon cancer. Remember me? Happy f'kin anniversary. Maybe see you in court.

"A POSSIBLY FATAL EVENT"

Guinea-pig Friday. Seven hours of waiting for a cautionary scan of my lungs and legs, all because I reported having shortness of breath this morning and my surgeon, Dr. Welton, and his resident scrunched their eyebrows like squirrels (if I'm a guinea pig, they're squirrels) and thought of the remote possibility of PE--pulmonary embolism--"a possibly fatal event."

I have a few risk factors, you see: an open line running into my veins for chemo; I have cancer; I am over forty years old; have an infection; and have been largely immobile. Better safe than dead, they think but don't say. (Reportedly, it's one of the most frequently missed diagnoses in medicine.) So there goes our Friday afternoon and evening. We wait, and wait, for a space in the CT queue . . . and Doc Daphne comes over from the hospital next door to try to help move things along . . . at 8:00 P.M. on a Friday night. Three kids she has at home, and she's with Paula and me. This is what you call care. This is what leads to Paula getting for her four Harry Potter T-shirts from her stash in London. My lungs and legs turn out to be clear.

A SOB STORY

Waking up with bad chemo/radiation nausea and diarrhea . . . an hour on the john to start the day . . . followed by thirty minutes of intense sobbing in bed, broken occasionally by heavy breathing (to relax me), the tears flow and I plead for "a break." I know part of this frustration is from yesterday's seven hours of helplessness and waiting for exams . . . and the possibility of "a fatal event," as if colorectal cancer isn't a possibly fatal event. I begin to view crying as part of healing. It's probably in the cancer-support books that the nurses gave me and that I've yet to read . . . Fourth, you cry.

LICK ME

After too many days of chemo/poison pumping through my veins, my body sends its first signal of being pissed off at the assault--a rash, or rawness, on the back and center of my tongue, all raised and ugly, what the doctor calls "mucousitis"; what a nurse says might be thrush . . . we'll worry about it tomorrow. Today, I'll just add some antibiotics to my arsenal to try and hit the elusive fever that kicks up each afternoon and evening, from 99.4 to 100.5 or so, possibly related to last week's discovery of an abscess. "Possibly," says Dr. Daphne and Dr. Welton. Lotsa possiblys in this long-term anti-cancer contest that's still in the early stages. Even a temporary alarm set off by Abbott--signaling occlusion in the tubes that send 5-FU chemo drug into my body--doesn't trip us up for long.

An 800 number, plus a knowing pharmacist on the "home health care/Life Care Solutions" hotline, helps us get Abbott back on track with only a ten-minute interruption in cancer-kick-butt service. With ER playing in the background on TV, my little emergency couldn't have asked for a more macabre backdrop. Blood and guts all over the Mitsubishi big-screen TV . . . a portable-CD-player-sized pump in my hands, sending peeling alarm signals and not responding to my attempted repair. And I can't very well call Dr. Greene.

I DON'T LIKE MONDAYS . . .

Setting the alarm for 8:45 A.M., which to the rest of the world sounds late, I know, but for someone who is woken up every two hours to take a piss because radiation waves have riled up my bladder tissue till it's as angry as an eighty-four-year-old's who's got a mean case of prostatitis . . . truth is, I don't want to arise at 8:45. I could easily sleep till 10:00, since I haven't enjoyed real REM-type sleep for what seems like a week.

Waiting for nurse Jerry, all earnest and bearded and careful and responsible-like, to come visit and slip on the rubber gloves and rip a bent needle out of the port that's been surgically implanted in my chest . . . new week, new bag of "dope" for my main man, Abbott. . . . It's all good, I suppose, but I don't enjoy lying flat on my back with anti-splash pads beneath my chest and torso. (Chemo is poison, let's remember; we don't want that shit splashing about the linens, much less our respective skins. . . .)

Mondays mean a whole week ahead of whomping the bad cells with good X rays and 168 milliliters of 5-fluorouracil cocktail, my chemo drug of choice . . . so by Friday night or Saturday morning, I will almost certainly feel like shit. Which means, they tell me, Mondays should actually be "good" days, because I've had the weekend off from the radiation assault . . . and my body's had a chance to "recover."

Shit, other than that, Mondays are fine specimens of the week. When you're normal, that is. When you're Cancer Boy, you're just a bit more skeptical about this fine day. . . .

BONDING

Flipping off a friend, in a good way, a male-bonding way, as I lie on the couch, fatigued and diseased. He's flown twenty-five hundred miles to visit me, my old roommate Todd, and at one point I look over at him in the living room, our eyes meet, and I give him the finger. He understands completely. What men want. A tough way to say, "Thanks for leaving your job and family for a few days to come hang with me as I get chemo'd and radiated." A guy thing. I love the guy. He's here. I'm hurtin'. So "Fuck you." Makes perfect sense, as Paula wonders, maybe, what in the hell I've just done to my friend. She understands, maybe not completely.